Reimagining Mobility in Smaller Cities

- connect2783

- Jul 22, 2025

- 10 min read

Updated: Aug 5, 2025

What does urban mobility look like when metros and flyovers aren't the norm? This article explores how people in India’s small and mid-sized cities move: on foot, by cycle, and through shared autos and e-rickshaws; and why these everyday modes are often missing from formal planning. Drawing from Nāgrika’s recent research and panel discussion, it highlights overlooked policy gaps, invisible data systems, and powerful community-led solutions that can shape a more inclusive and grounded mobility future for small cities.

In India’s small and mid-sized cities, urban mobility is shaped by people, proximity, and practicality. Most people living in these cities walk, cycle, or depend on shared autos and e-rickshaws to get to work, school, or the market. Yet, the mobility needs of the people in these cities are often left out of mainstream transport planning conversations. The cities remain data-deficient, policy-invisible, and structurally underserved.

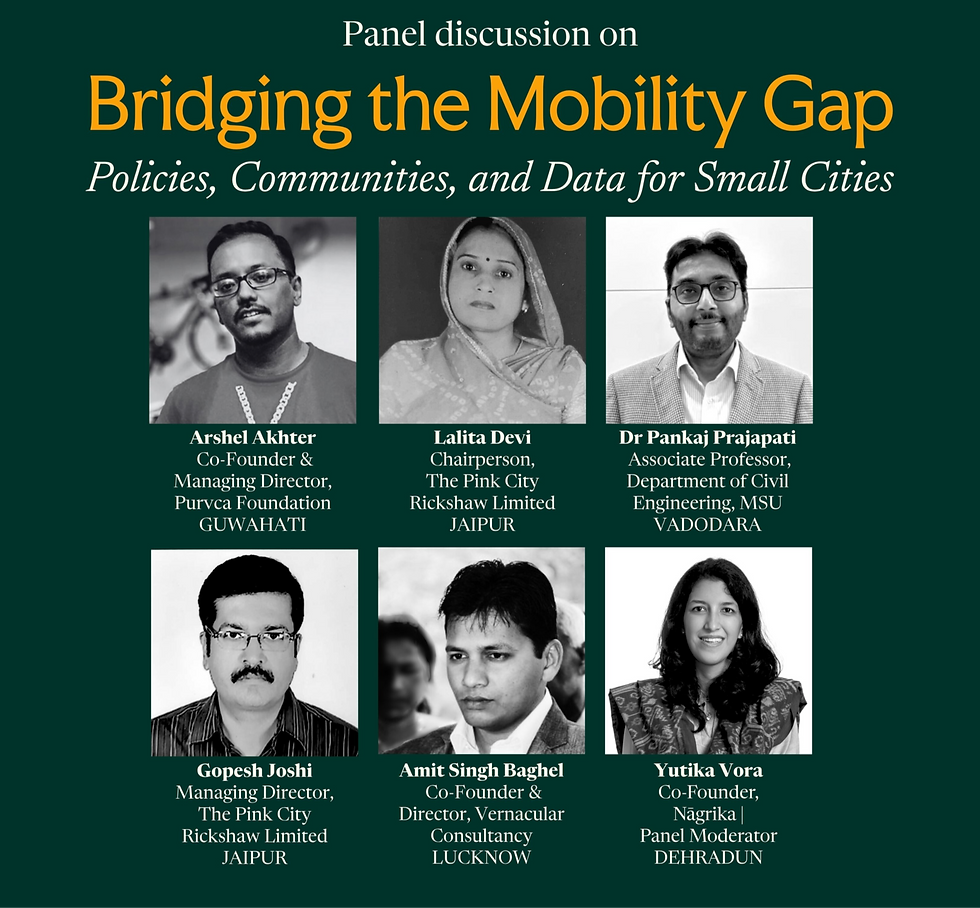

On 10th July 2025, Nāgrika hosted a panel discussion titled “Bridging the Mobility Gap: Policies, Communities, and Data for Small Cities.” The event brought together experts, practitioners, and researchers to reflect on the systemic mobility challenges in smaller cities. Grounded in findings from Nāgrika’s research on mobility in small and mid-sized cities, the session centred around three core themes: policy frameworks, data and research gaps, and community-led solutions.

As part of this effort, during the session we launched the first two reports highlighting mobility needs of those living in smaller cities. An in-depth examination of how mobility functions in places that often remain invisible in national and state-level transport planning.

This article brings together our research insights, reflections from the panel, and broader learnings on how small cities can shape a new mobility narrative.

Learning 1: Build policy frameworks that support what already works

Most of the mobility needs in smaller cities are being met through everyday adaptations, despite the absence and inadequacy of state-run systems. Walking, cycling, and Intermediate Public Transport (IPT) modes like e-rickshaws and shared autos are doing the heavy lifting.

According to our analysis:

Nearly half of all trips in small cities are on foot, compared to about 40% in metro cities.

Two-wheelers account for 27% of trips, while buses serve just 4%.

E-rickshaws and shared autos fill crucial gaps, offering flexibility where buses and metros do not exist or do not reach.

These modes are often ignored as “informal” or “temporary,” yet they form the backbone of mobility in cities like Patna (38% IPT mode share), Ranchi (28%), and Visakhapatnam (38%). Ignoring them in planning means ignoring how the majority of people actually move.

A standout example of system-level support comes from Bhubaneswar, where the Capital Region Urban Transport (CRUT) has actively integrated IPTs into the formal public transport system. Its ‘Mo E-Ride’ initiative is an e-rickshaw feeder service that complements the ‘Ama Bus’ (formerly known as ‘Mo Bus’) network, helping bridge the last-mile gap (final stretch of a journey between a public transport stop and one’s home, workplace, or destination). CRUT’s model illustrates how public institutions can work with existing modes, instead of replacing them, offering dignity to drivers and improving accessibility for users.

In contrast, Guwahati illustrates what happens when such integration is missing. Despite central and state schemes, the city lacks a dedicated transport planning cell. Instead, the focus lies in increasing vehicle registration, an outcome of revenue-centric governance, as noted by Mr. Arshel Akhter. Guwahati, with a population of 15 lakh, has 15.6 lakh registered vehicles (more than one per person), signalling a growing reliance on private modes. Meanwhile, the public bus services remain grossly inadequate: the city has only 550 buses (including 200 e-buses under the PM eBus Seva scheme), falling far short of the 800 buses it actually needs.

This vehicle-centric approach is further reflected in the continued investment in flyovers and big-ticket infrastructure, even though infrastructure for walking and cycling (despite accounting for a significant share of daily trips) remains neglected.

These highly visible projects offer limited value in improving everyday mobility and often come at the cost of more accessible, people-centric solutions.

Additionally, despite IPT accounting for around 20% of total trips, many modes like pedal and battery rickshaws remain unregistered and unaccounted for, leaving significant blind spots in both planning and regulation. Unlike Bhubaneswar, where e-rickshaws have been formally integrated into public transport, Guwahati continues to depend on these modes without recognising or supporting them structurally.

Mr. Arshel Akhtar further mentioned that even where contracts are awarded to run city buses, the model of engagement matters. Net Cost Contracting (NCC), where private operators bear all costs and retain fare revenues, still dominates in many cities, including Guwahati. This often leads to cherry-picking profitable routes and weak public accountability. In contrast, Gross Cost Contracting (GCC), where the government pays operators a fixed fee and retains fare control, offers better transparency, route coverage, and service quality. Yet, this model remains underutilised.

Even in cases like Jaipur’s Pink City Rickshaw Company (PCRC), which has shown how IPT can support inclusive employment and mobility, the lack of formal recognition has limited its potential. As the panel discussed,

Success stories should not have to rely on informal support or political goodwill to thrive; they need formal structures that protect and strengthen them.

Smaller cities don’t need completely new systems directly imposed from above; they need policies that acknowledge and build upon what already works. When walking, cycling, and IPT modes are treated as core systems rather than temporary solutions, and when governments invest in strengthening these modes through formal recognition, regulation and support, cities become more accessible, inclusive, and sustainable.

Learning 2: Replace assumptions with evidence in data gaps

Why do cities that clearly rely on walking, cycling, and IPTs end up building elevated flyovers, metros, or dismantling BRT systems? A big part of the answer lies in how data is collected, interpreted, and used (or misused). Our panellist, Mr. Amit Singh Baghel, dwelled on this and highlighted how data in smaller cities often suffers from three layers of distortion:

Data collection to justify decisions, not inform them. Authorities may already have projects in mind, and surveys become a rubber stamp.

Planning processes that lack sequencing. The Comprehensive Mobility Plan (CMP), Alternative Analysis, and Detailed Project Report (DPR) are meant to be sequential. But in practice, they are often drafted simultaneously, weakening their integrity.

Lack of genuine citizen participation. Surveys often ask questions like “Would you ride a metro if it came to your city?” Naturally, most say yes. But a more insightful question might be, “If your city had ₹X crores for development, how would you spend it?” This broader framing reveals whether people truly prioritise transport over other needs like housing, health, or education or prioritise other ways of transport over the ones which are decided for them.. Narrow transport-focused surveys can misrepresent local preferences and create planning bias.

These aren’t theoretical issues. In Surat, for instance, the expected BRTS ridership was 2.8 lakh, but the actual figure hovers around 90,000. Why? Poor route optimisation, weak land-use integration. Meaning that the transport system (like BRT routes) was not always properly aligned with how and where people live, work, study, or shop in the city. So even if buses were running, they didn’t connect well to busy neighbourhoods, office hubs, markets, or schools. This mismatch meant fewer people found it useful, and ridership stayed low. It also reflects a bias toward visible, capital-heavy projects that offer political mileage, even when they fail to meet actual mobility needs.

Smaller cities don’t need completely new systems directly imposed from above; they need policies that acknowledge and build upon what already works.

Similarly, Metro systems also continue to be pursued even in low-density cities, ignoring the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs’ Metro Rail Policy (2017), which designates metro rail as a last-resort option. In practice, the policy is often bypassed.

Another key issue flagged by Dr. Pankaj Prajapati was the access to data itself. While cities like Ahmedabad have mechanisms for data sharing (especially for BRT), many others guard ridership, ticketing, and performance data tightly. Often, inflated figures are presented to justify ongoing projects, while underperforming systems are dismantled without proper evaluation. This has been evident in cities like Indore and Bhopal, where BRT corridors were either abandoned or scaled back prematurely, not necessarily due to inherent flaws in the system, but because of poor execution and a lack of transparent public audits.

Meanwhile, in Guwahati, data gaps further compound governance challenges. While the city technically has IPT services, many of these (such as battery and pedal rickshaws) are not registered, which means their usage is not measured, studied, or planned for, even though they play a central role in the city’s daily movement. Without recognition in official data, these modes remain invisible in funding and planning.

It is only when evidence-based decision-making is institutionalised and when citizens’ lived experiences shape the data that is collected that cities can design mobility systems that actually help people of those cities live better lives.

In contrast, the road safety data (such as accidents and FIRs, etc.), unlike mobility data, is sometimes easier to access. Gujarat, for instance, established a Road Safety Authority in 2018, which shares FIR and crash data with relative ease (Tamil Nadu was the first to set up such an authority in 2007). This contrast highlights that when governance mechanisms are in place, transparency and accountability naturally improve.

Smaller cities need data systems that are transparent, inclusive, and responsive to ground realities. Planning that rests on flawed or unavailable data may end up misallocating resources and misrepresenting citizen needs. Informal and non-motorised transport modes must be made visible in data and included in analysis and projections. It is only when evidence-based decision-making is institutionalised and when citizens’ lived experiences shape the data that is collected that cities can design mobility systems that actually help people of those cities live better lives.

Learning 3: Transport planning needs to engage citizens meaningfully

Most small and mid-sized cities don’t suffer from a lack of ideas; instead, they suffer from a lack of listening. The panel repeatedly came back to this: cities must stop planning in isolation and start engaging citizens and communities in a meaningful way. Community participation emerged as both a solution and a missing link in mobility governance.

Take Ernakulam, for example. When the Kerala State Transport Department invited suggestions on underutilised bus routes, the public responded in force. Residents asked for feeder services to better connect homes to metro stations and offices. As a result, 25 new routes were prioritised. Based on real need, not just projections.

Another leading example is Bhubaneswar, where the CRUT’s public transport transformation shows what’s possible when citizens' needs shape system design. The Ama Bus and Mo E-Ride services are integrated, gender-inclusive, and responsive, and the city has invested in real-time data, digital ticketing, and last-mile solutions. Over 1 lakh passengers use the service daily, and public feedback has helped continually improve routes and services.

These examples show that context-specific, community-driven solutions work best. Whether through participatory mapping, citizen audits, or neighbourhood transport plans, inclusion leads to smarter outcomes.

Mr. Gopesh Joshi offered a powerful example of how community-led transport initiatives can reshape public space. The Pink City Rickshaw Company (PCRC) was founded in Jaipur and led by women from marginalised communities. It provides eco-friendly e-rickshaw tours while also breaking gender norms in mobility. The presence of women e-rickshaw drivers has visibly shifted the perception of public spaces. PCRC not only trained women in driving but also in safety, first aid, and harassment handling. Community trust builds from the ground up, and riders often feel safer when they see women behind the wheel.

The discussion also underlined the need to move beyond token public consultations. Whether through neighbourhood-based planning or citizen-led accessibility mapping, participation must be embedded into the core of mobility governance. Not only does this lead to better outcomes, but it also legitimises the lived experience of everyday users.

Meaningful participation is about building systems that listen, respond, and adapt with citizens. When citizens are treated as co-creators, mobility systems become more inclusive, relevant, and sustainable. For small cities (where formal structures may be limited and resource-constrained), community-driven governance becomes essential rather than desirable.

Learning 4: Copy-paste models don't work in hill cities

The conversation also extended to hill cities (particularly, places like Gangtok, Dimapur, and towns in the Northeast), which face entirely different constraints. Here, roads are narrow, ridership is scattered, and public transport options are minimal.

As some participants highlighted during the panel, taxis dominate but are expensive and monopolised. Government-run buses are few, and corridor-based solutions like ropeways, while visually appealing, are limited in scale and scope.

Experts pointed out that hill cities don’t need grand solutions; they need adaptive thinking. Ropeways are capital-intensive and can’t serve dispersed neighbourhoods. Instead, smaller vehicles, route sharing, and localised mobility services may be more effective.

The panel stressed the importance of breaking monopolistic control, involving NGOs and local media in advocacy, and encouraging local entrepreneurs and policymakers to co-create viable, terrain-sensitive contextual alternatives. It also means addressing regulatory gaps, such as who is responsible when fleet owners rent e-rickshaws to drivers with little training or oversight.

Hill cities demand mobility approaches tailored to their terrain and social fabric. Copying models from the plains does not work.

Reframing Mobility with Small Cities at the Centre

Through this panel discussion and our broader research, the case for a small city-specific mobility narrative is clear. Smaller cities don’t need scaled-down versions of big-city systems. They need transport ecosystems built on their realities: short trip lengths, mixed land use, trip chaining, high rates of walking and IPT use, and deeply localised needs.

Key Takeaways

Data must reflect lived realities, not assumptions or hidden agendas.

E-rickshaws, walking or rickshaws (IPTs and NMTs) are not temporary solutions; they are core systems in reality.

Lack of formal recognition of small city mobility systems creates serious regulatory and safety risks. Without legal backing, both users and operators remain vulnerable, with no clear accountability, oversight, or enforceable rights.

Community participation must be integral, not symbolic.

Public investment in what already works, instead of chasing prestige projects

Hill cities require tailored approaches, not replications of plains or metro templates.

To put it simply:

Mobility in smaller cities is more than a matter of movement or fancy infrastructure; it is a matter of access, equity, and dignity. When cities listen to their people, prioritise their needs, and support their existing systems, transformation doesn’t have to be expensive. It just has to be thoughtful.

At Nāgrika, we believe that to bridge the mobility gap, cities must start by valuing the everyday systems that already keep these cities moving. And that begins by listening.

Comments