Citizen Powered Governance

- connect2783

- Dec 5, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Jan 9

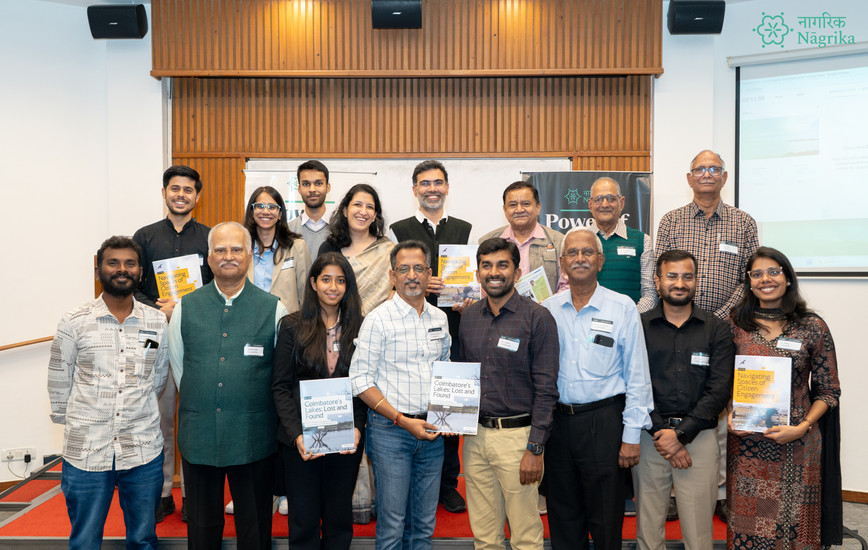

India’s smaller cities are witnessing a rapid transition in both physical and social infrastructure. While government agencies try to catch up with this transition, citizens in these cities are gaining power. They are helping to balance this shift. Citizens, neighborhood groups, and local organizations are actively engaging with their cities. They are redefining how governance is practiced. This was evident during Nāgrika’s “Power of Small Cities 2025” roundtable, held in New Delhi. The gathering brought together practitioners and academics from cities like Udaipur, Coimbatore, Pampore, Bhuj, and Gangtok. Its deeper purpose was far more ambitious: to collectively imagine what citizen-powered governance can look like for India’s smaller cities in the decade ahead.

Reframing Governance from the Ground Up

One of the strongest ideas that surfaced was that the Power of Nāgrika, i.e., citizens, is not abstract. It is functional in how people act for their cities. This can be seen in early-morning lake patrols, the painstaking mapping of forgotten channels, or the weekly gatherings of volunteers to clean, document, or protect ecological spaces like lakes or rivers.

Participants emphasized that when citizens engage in such work consistently, they begin to perform functions that public institutions should fulfill but often cannot. They document more regularly. They respond more quickly. They hold the memories of places that outlast administrative turnover. They remain when departments shift priorities or when political winds change direction.

This creates systems of care that eventually influence the shape, priorities, and accountability of formal institutions. It is starting to feel like a governance system that ought to be noticed and integrated into what we traditionally call governance.

Technical Knowledge, Citizen Expertise

Amid changing systems of citizen action, technical knowledge has quietly become a form of civic power. In the context of urban lakes, what once began as citizens asking for institutional attention is now reshaping into citizens offering knowledge that institutions increasingly rely on. This expertise is built through the slow accumulation of context-specific understanding of cities. It includes the collection of information that official data often misses, mapping patterns that are otherwise unseen, and careful documentation that traces the movement of wastewater or the behavior of a stream across seasons.

Equally important are the grounded personal practices, such as daily walks around lakes, repeated observations, and intimate familiarity with the land. These practices allow residents to recognize subtle changes long before they are registered and noticed in formal systems.

This form of technical engagement has strengthened a culture of restoration. Small demonstrations can build credibility, secure permissions, and create room for collaborative planning. It signals a shift in who holds actionable knowledge in a city and how that knowledge circulates.

Participants also recognized the delicate nature of these partnerships. Political pressures, commercial interests around ecological spaces, and shifting administrative priorities can all unsettle the trust and momentum that collaborative work requires. In this landscape, the functional independence of civic groups becomes essential. This independence is not a stance of opposition but a way of protecting the neutrality and integrity of the knowledge they produce.

Peer Learning as Infrastructure

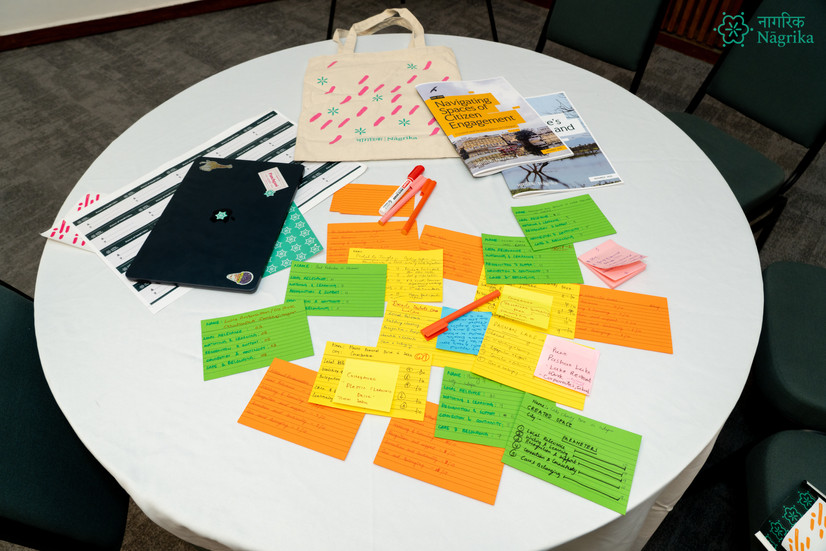

Another idea that surfaced strongly was the powerful role of peer learning. The Nāgrika-Connect roundtable offered not merely a forum but a space (one not shaped by institutional agendas or formal hierarchies) where people could think, share, and learn together. In this co-created environment, participants found room for candid reflection, the exchange of hard-earned lessons, and the freedom to test ideas without the pressure of official expectations.

Citizens from different cities shared the challenges of sustaining motivation over the years. They reflected on burnout and cynicism, yet noted how small but visible wins keep communities committed.

Such spaces, as curated during this roundtable, are especially vital for small cities. Civic efforts often work in isolation, and national conversations tend to be dominated by metropolitan narratives. Here, lived knowledge is not only shared but also recognized as expertise in its own right. The roundtable affirmed that peer-learning ecosystems are more than supportive networks; they are a form of infrastructure. They enable inclusive ecological governance by connecting people, practices, and insights that rarely meet in formal settings.

Persistence as Civic Power

Across discussions, persistence emerged as one of the most understated yet defining forms of civic power. It became clear that meaningful change in ecological spaces is rarely the result of a singular intervention. It is the work that continues after the excitement fades, after permissions stall, and after opposition gathers strength. Many groups spoke of years, sometimes decades, spent navigating shifting bureaucracies, uneven funding, community fatigue, and pressure from vested interests.

In this light, persistence appears less as endurance and more as a civic craft. It is the ability to rebuild momentum after setbacks, to re-engage communities when interest wanes, and to keep tending to a place even when progress is imperceptible. This steady continuity of care allows citizen efforts to mature from scattered acts of volunteerism into something resembling governance. It is a slow, patient shaping of outcomes that only sustained commitment can produce.

Looking ahead, the roundtable made clear that citizens are not peripheral to governance; they are central actors who shape city futures through everyday practices of stewardship, documentation, monitoring, and advocacy. Their contributions expand the definition of governance itself. Governance is not limited to offices or formal mandates but is equally produced through sustained civic action. Nāgrika-Connect is taking this scattered brilliance and turning it into a visible, connected, and influential force. Its mission is to amplify citizen power, strengthen citizen networks, mainstream citizen knowledge, and build an ecosystem of community-driven city learning and action. By making citizen initiatives legible, respected, and institutionally recognized, our initiative aims to shift how governance itself is understood. We are committed to bringing citizens to the center of India’s urban story and to scaling the platforms, partnerships, and knowledge systems that will make their power impossible to overlook.

Comments